In the acute phase of articular cartilage damage, the treatment consists of resting the joint, elevation, ice, compression, anti-inflammatories and routine physiotherapy modalities. As the swelling and pain diminish, it is important to commence a range of motion exercises to regain movement of the knee fully.

Occasionally in the situation of a tense haemarthrosis, the knee can be aspirated under sterile conditions to remove the blood from within the joint, and some local anaesthetic can be injected into the knee to help with pain relief. The aspirated blood should be placed into a container and left to stand. If the injury involves a fracture of the underlying bone, in other words, if the damaged fragment that has been knocked off includes cartilage and bone, then usually droplets of fat from the bone marrow are released into the knee and these are visible in the aspirated fluid and will float to the top pf the aspirated blood if left to stand.

The subsequent management of this condition depends on whether the presentation is acute or chronic.

Acute treatment

The treatment in this situation depends on the size and thickness of the fragment that has been knocked off and the age of the patient.

- In a child with open growth plates, if a full-thickness piece of articular cartilage has been knocked off to expose the underlying bone and the fragment is of a large enough size, it may be worth operating on the knee to find the loose fragment and reattach it to its original bed and hope that the articular cartilage fragment will heal to the underlying subchondral bone. This does not always occur and should it not heal down and continue to cause symptoms, then the piece will have to be removed. In a child, it is certainly worth attempting to reattach the fragment.

- In an adult with closed epiphyses, if the piece that has been knocked off is purely articular cartilage, then this piece should be simply removed and the donor bed of bone can be treated appropriately, as in the case of a chronic osteochondral fragment. In the adult, the articular cartilage really has no capacity to heal to the subchondral bone and attempting to reattach it is usually a futile exercise which will cause the injured person ongoing pain and instability type symptoms and further locking should the piece fall off again.

- If the chondral piece is associated with a significant fragment of osteochondral bone, and the piece is large enough, over 2 cm in diameter, then it is certainly worth attempting to reattach the fragment and fix it in place in both the adult and child. The bone fragment will certainly heal to the underlying bone, but whether the overlying cartilage will heal and attach to the surrounding cartilage, is not guaranteed, but it is worth trying due to the underlying bone attachment. If the underlying cartilage fragment does not heal, then once again, this can be removed at a later stage and treated as for a chronic injury.

Chronic Injuries

The acute phase treatment outlined above can certainly be attempted within the first seven to ten days of an injury of the knee. If there is a large attached bony piece to the articular cartilage fragment that has been knocked off, then given up to two weeks, it may be feasible to reattach it. However, once beyond this point, there is really not much point in attempting to reattach the fragment as it is unlikely to heal, and in this situation, chronic treatment options are used.

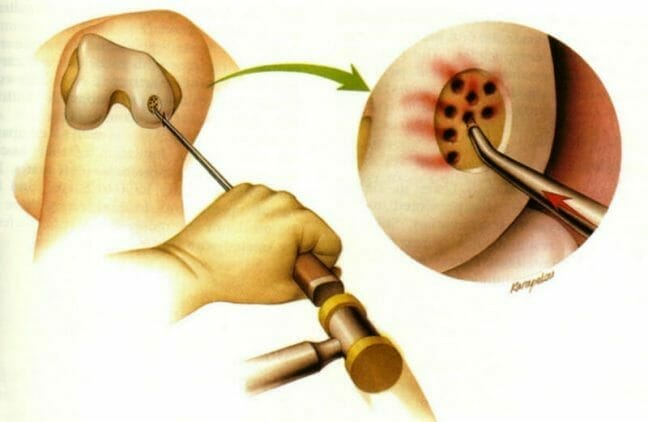

- If there is a loose piece within the knee of articular cartilage and/or bone, this is removed. The exposed bone bed is then treated using a debridement (tidying up) of the edges of the articular cartilage fragment to trim any loose pieces or flaps of articular cartilage. The bone bed can be microfractures or drilled. The aim of this technique is to cause infill into the osteochondral defect, which usually will occur with fibrous (scar) tissue.

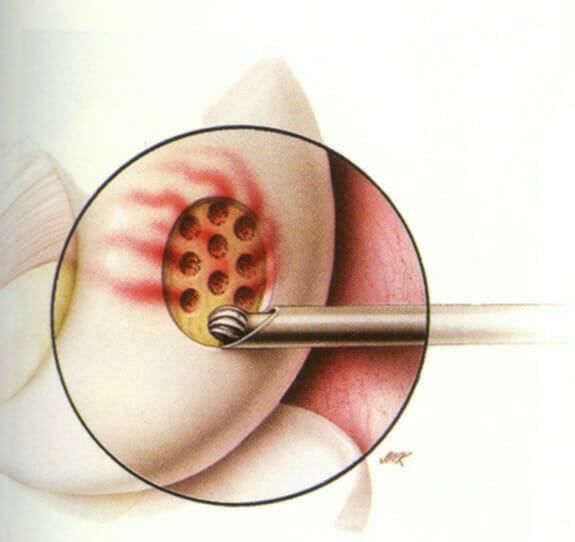

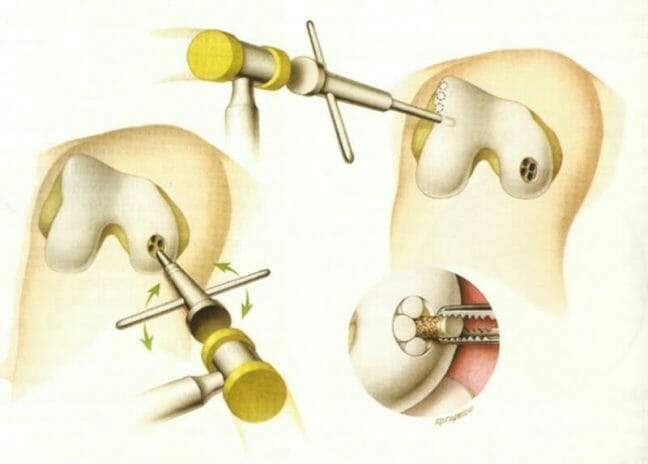

- Other options for the chronic situation include mosaicplasty, which involves taking a plug or plugs of articular cartilage and bone from elsewhere within the knee and transplanting these into the defect.

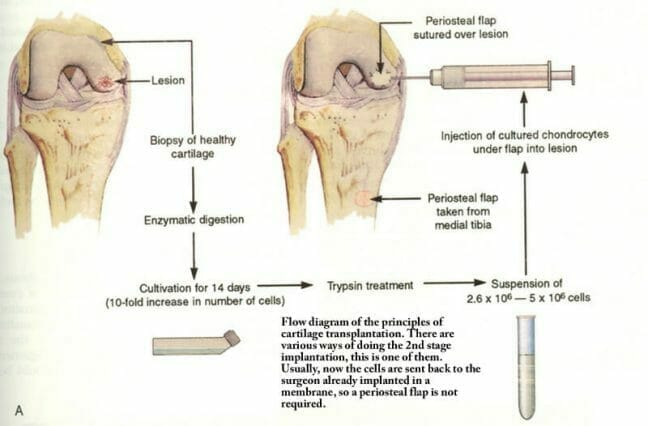

- Another, more debated, and currently state of the art, technique would be to undertake autologous articular cartilage transplantation, the theory of which would be to cause normal hyaline articular cartilage to re-grow in the defect.

It is important to address any underlying ligament instabilities either at the same time or shortly afterward so as to stabilise the knee and to protect whatever technique of treatment that has been undertaken to the articular cartilage damaged area. This may include anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and patellofemoral stabilisation.

There is debate as to the treatment for asymptomatic lesions, but if they are small in size there is some literature to suggest that they should be left alone. The treatment options for isolated articular cartilage lesions include:

Rehabilitation following Articular Cartilage Surgery

The rehabilitation in the acute phase involves reducing swelling and pain and regaining motion, muscle strength, balance and coordination.

If the articular fragment has been reattached, post-operative rehabilitation would include a period of non-weight bearing on crutches of between two to four weeks, during which time range of motion exercises are continued. Twisting motions and kneeling/squatting are prohibited to prevent shear forces across the reattached fragment for once again, between four to six weeks.

Following the two to four week period of time, weight bearing is commenced from partial to fully weight bearing as tolerated, using crutches. The rehabilitation is progressed to increase strength, balance and coordination using physiotherapy modalities and exercise/gym equipment.

With an attached boney fragment, this should certainly heal to the underlying bone bed within six weeks. The articular cartilage reattachment on its own without a bony fragment can take up to eight to twelve weeks. Twisting, turning and impact sports are usually gently recommended from about three months onwards depending on the underlying surgery and aetiology of the osteochondral injury.

In the chronic situation following articular cartilage debridement, microfracture, mosaicplasty or chondrocyte transplantation, once again the initial rehabilitation involves reducing swelling and controlling pain with the use of anti-inflammatories, a TED stocking and a Cryocuff.

The patient is mobilised non-weight bearing for a period of two to six weeks, dependent on the size and depth of the lesion. Once this period is over, increased weight bearing is commenced over a period one to two weeks, and increasing resistive non-impact loading exercises are continued. Twisting and pivoting sports are generally returned to within three to five months, dependent upon the completion of appropriate muscle strengthening, balance and coordination exercises, as well as progressing through a sports-specific rehabilitation programme.

If there is an associated ligament injury, such as an anterior cruciate ligament injury, I usually will not reconstruct this at the same time as treating the articular cartilage injury. The reason for this is that the rehabilitation is contradictory for the two conditions, and it is important not to jeopardise the rehabilitation of one condition due to a concurrent treatment that has been undertaken for something else. Therefore the articular cartilage lesion can be treated and rehabilitated. Once this has been done, the cruciate ligament reconstruction and/or treatment of the patellofemoral joint can be undertaken.

In certain situations following treatment of an osteochondral injury, it may be appropriate to use an offloading brace, which diminishes the force on the appropriate compartment of the knee, where the osteochondral damage occurred and mobilisation may be commenced at an earlier stage. The problems with an offloading brace are that it can be quite uncomfortable, and can cause pressure on the knee where the forces are applied to offload the knee. It can also cause a reduction in knee movement if the range of motion exercises are carried out in the brace. The braces are also expensive. Following successful microfracture, articular cartilage infill can occasionally be demonstrated on a high-resolution MRI scan. This can also be demonstrated following articular cartilage transplantation.

The appropriate treatment for you depends on many factors and will have to be assessed by the specialist treating you. Price packages will be personalised to you and your needs. We also work with multiple hospitals to offer our patients a price match service. Please get in touch if you wish to book a consultation with Professor Jari, one of Manchester’s leading Knee Surgeon.

Make An Enquiry

Or contact us directly

[email protected]

0161 445 4988